Deborah Cameron, Tokyo

July 8, 2006

TWENTY-FIVE years ago Tetsuro Tanaka, an engineer,

was fired from hisjob for refusing to take part in compulsory

morning callisthenics.

Since then, every working day, he has gone to the company gate

at 8amand sung protest songs for half an hour. Once a month, on

theanniversary of his sacking, he sings all day.

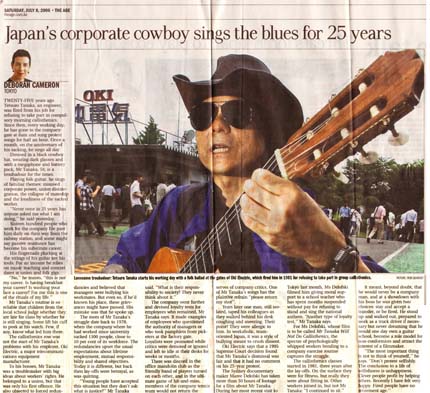

Dressed in a black cowboy hat, wearing dark glasses and with a megaphone and battery pack, Mr Tanaka, 58, is a troubadour for the times.

Playing folk guitar, he sings of familiar themes: misused corporate power, union disintegration, the collapse of mateship and the loneliness of the sacked worker.

"Never once in 25 years has anyone asked me what I am doing," he said yesterday.

Sixteen hundred people who work for the company file past him daily on their way from the railway station, and some might say passive resistance has become his substitute career.

His fingernails plucking at the strings of his

guitar are his tools.

For an income he relies on music teaching and concert dates at

union and folk gigs.

"No," he insists, "this is not my career. Is having breakfast your career? Is washing your face a career? For me this is one of the rituals of my life."

Mr Tanaka's routine is so reliable that children

from the local school judge whether they are late for class by

whether he is still singing.

Some lift his cuff to

peek at his watch. Few, if any, know what led him there.

The callisthenics row was not the start of Mr Tanaka's problems with his employer, Oki Electric, a major telecommunications equipment manufacturer.

To his bosses, Mr Tanaka was a troublemaker with big ideas about workers' rights. He belonged to a union, but that was only his first offence. He also objected to forced redundancies and believed that managers were bullying his workmates. But even so, if he'd known his place, these grievances might have passed. His mistake was that he spoke up.

The roots of Mr Tanaka's struggle date back to 1978, when the company where he had worked since university sacked 1300 people, close to 10 per cent of its workforce.

The redundancies upset the usual expectations about lifetime employment, mutual responsibility and shared objectives. Today it is different, but back then lay-offs were betrayal, as was quitting.

"Young people have accepted this situation

but they don't ask: what is justice?" Mr Tanaka said. "What

is their responsibility to society?

They never think about it."

The company went further and devised loyalty tests for employees who remained, Mr Tanaka says. It made examples of employees who questioned the authority of managers or who took pamphlets from picketers at the factory gate. Loyalists were promoted while critics were demoted or ignored and left to idle at their desks for weeks or months.

There was discord in the office mandolin club as the friendly band of players turned on each other, and in the ultimate game of hit-and-miss, members of the company tennis team would not return the serves of company critics. One of Mr Tanaka's songs has the plaintive refrain "please return my shot".

Years later one man, still isolated, taped his colleagues as they walked behind his desk coughing and sneezing. Their point? They were allergic to him. In workaholic, team-oriented Japan, it was a style of bullying meant to crush dissent.

Oki Electric says that a 1995 Supreme Court decision found that Mr Tanaka's dismissal was fair and that it had no comment on his 25-year protest.

The Sydney documentary maker Maree Delofski has taken more than 30 hours of footage for a film about Mr Tanaka. During her most recent visit to Tokyo last month, Ms Delofski filmed him giving moral support to a school teacher who has spent months suspended without pay for refusing to stand and sing the national anthem. "Another type of loyalty test," Mr Tanaka says.

For Ms Delofski, whose film is to be called Mr Tanaka Will Not Do Callisthenics, the spectre of psychologically whipped workers bending to a company exercise routine captures the struggle.

The callisthenics classes started in 1981, three years after the lay-offs. On the surface they were for fitness, but really they were about fitting in. Other workers joined in, but not Mr Tanaka: "I continued to sit."

It meant, beyond doubt, that he would never be a company man, and at a showdown with his boss he was given two choices: stay and accept a transfer, or be fired. He stood up and walked out, prepared to work as a truck driver if necessary but never dreaming that he would one day own a guitar school, become a role model for non-conformists and attract the interest of a filmmaker.

"The most important thing is not to think of yourself," he says. "Don't protest selfishly. The conclusion to a life of selfishness is unhappiness. Clever people profit by helping others. Recently I have felt very happy. Fired people have no retirement age."