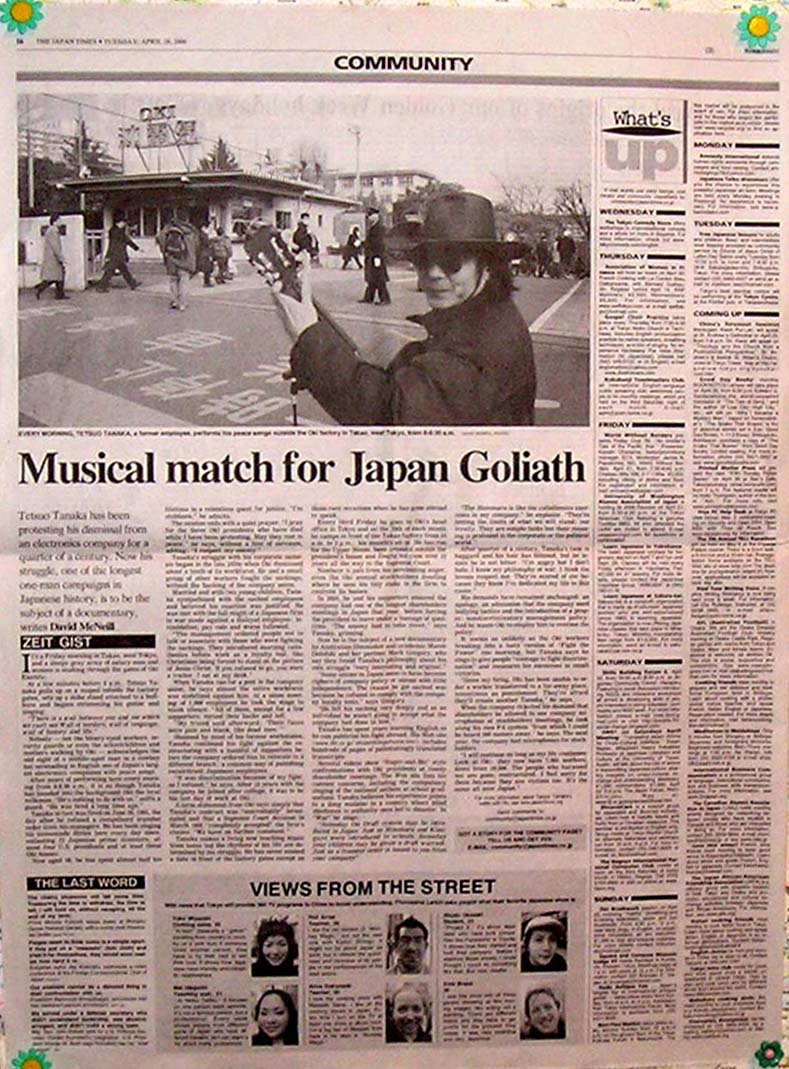

It’s a Friday morning in Takao, west

Tokyo and a sleepy grey army of salary-men and women is snaking

through the gates of Oki Electric.

At a few minutes before 8 a.m., Tanaka Tetsuo pulls up on a moped

outside the factory gates, sets up a mike stand attached to a

bullhorn and begins strumming his guitar and singing:

There is a wall between you and me which we can't see

Wall of borders, wall of language, wall of history and life

Nobody - not the bleary-eyed workers, security guards or even the schoolchildren and mothers walking by Oki - acknowledges the odd sight of a middle-aged man in a cowboy hat crooning peace songs in English before one of Japan's largest electronics companies.

After years of performing here every morning from 8 - 8.30am, it is as though Tanaka has blended into the background like the local milkman. "He's nothing to do with us," sniffs a guard. "He was fired a long time ago."

Tanaka in fact was fired on June 29, 1981, The day after he refused a compulsory transfer order from his managers. He has been singing his homemade ditties every day since, outlasting 13 Japanese prime ministers, almost four US president and at least three Oki bosses. Now aged 58, he has spent almost half his lifetime in a relentless quest.

"I'm stubborn." he admits.

The session ends with his favorite classical guitar tune, The memory of Alhambra, expertly played but lost in the din of passing traffic, follow by a quiet prayer.

" I pray for the three Oki presidents who have died while I have been protesting. May they rest in peace." he say, without a hint of sarcasm, adding " I respect enemy."

Tanaka’s struggle with his corporate nemesis began in the late 1970s when Oki dismissed about a tenth of its workforce. He and a small group of other workers fought the sackings, without the backing of the company union.

Married and with two young children, Tanaka sympathized with the sacked employees. He was met with the full might of a Japanese firm in war mode against a disloyal employee. Intimidation, pay cuts and worse followed, he claims.

"The management ordered people not to talk or associate with those who were fighting the sackings. They introduced morning calisthenics before work as a loyalty test, like Christians being forced to stand on the picture of Jesus Christ. If you refused to go, you were a traitor. I sat at my desk."

When Tanaka ran for a post in the company

union, he says almost the entire workforce was mobilized against

him. At a union meeting of 1000 employees he took the stage to

blank silence. “All of them, except for a few supporters, turned

their backs and left. My friend said afterward. 'their faces were

pale and blank. like desd men'"

Shunned by most of his former work mates, Tanaka continued his

fight the restructuring with a handful of supporters before the

company ordered him to relocate to a different branch, a common

way of punishing recalcitrant Japanese employees.

"It was discrimination because of my fight, so I refused." he says. After 12 yeas with the company he joined after college, it was to be his last day of work at Oki. The following morning he was in front of the factory demanding to be let in and imploring the employees to stand and fight.

A terse statement from Oki's PR division says simply that Tanaka's contract was 'unavoidably' terminated after declining the order to move, and that a Supreme Court decision in March 1995 "completely accepted" the firm’s claims. "We have no further comment."

Tanaka makes a living now teaching music

from home but the rhythms of his life are determined by his struggle.

He has never missed a date in front of the factory gates except

on those rare occasions when he has gone abroad to speak. "I've

arranged my life around this. If I feel a cold coming on I'll

go to bed early so I don’t miss my morning appointment."

Every third Friday he goes to Oki’s head office in Tokyo and on the 29th of each month he camps in front of the Takao factory from 10am to 3pm: his monthly sit-in. He has run for Upper House election, debated with senior politicians, been arrested outside the president's house and fought and lost his case over 12 years all the way to the Supreme Court.

Nowhere is safe from his unrelenting anger, not even the Oki annual stockholders meeting where he uses his tiny stake in the firm to confront its bosses. In 2003, he and his supporters stretched the talks out to over three hours, one of the longest shareholders meetings in Japan that year, before forcing the president to leave under a barrage of questions. "The enemy had to take cover," says Tanaka, smiling. Oki now has a three-minute speaking rule at its public meetings, which it flashes around the hall on giant video screens.

Tanaka now is the subject of a new documentary by Australian filmmaker and academic Maree Delofsky and her husband Mark Gregory, who say they found Tanaka’s philosophy about his own struggle "very interesting and unusual." This philosophy, published on his homepage ((http://www.din.or.jp/~okidentt/eigohome.htm) warns against the dangers of political vanity, losing sight of goals and of developing hatred for the 'enemy'

One section reads:

Find virtue in your enemy, find evil

in yourselves.

Usually people think they are right, and that enemies are wrong.

But there is no person 100% good or 100% wrong.

"Some unions in Japan seem to have become ciphers of company policy or unions with little independence. The reason he got sacked was because he refused to comply with the company loyalty tests," said Mark Gregory by phone from Australia. "He felt his sacking very deeply and as an individual he wasn’t going to accept what the company had done to him. He has built his life around that."

Gregory believes Tanaka has remained true to himself, despite the lonely, punishing road he has chosen. "Someone who has been doing this for so long; there might be a tendency to think of them as a crank. But the more you know him the more you realize that this is certainly not the case at all."

Tanaka has spent years learning English so he can publicize his fight abroad. His website includes hundreds of pages of painstakingly translated transcripts and subtitled videos. Several show 'Roger-and-Me' style confrontations with Oki presidents at rowdy shareholder meetings where he is inevitably bundled out, shouting at the top of his lungs, by security guards.

The website lists his lyrics and current concerns, which include changes to the Constitution and a call to end the compulsory singing of the national anthem at school graduation ceremonies. Tanaka believes his experience points to a deep malaise in a country where blind obedience to authority once led to disaster. In 'War' he sings:

Someday the Draft system may be introduced in Japan.

Just as hinomaru and kimigayo were introduced in schools.

Someday your children may be given a draft warrant.

Just as a transfer order is issued to you from your company

"The hinomaru is like the calisthenics exercises in my company," he explains. "They're testing the limits of what we will stand; our loyalty. They are simple tasks but their meaning is profound in the corporate or the political world."

After a quarter of a century, Tanaka's face is haggard and his hair has thinned, but he insists he is not bitter. "I'm angry but I don't hate. I know my philosophy of war. I think the bosses respect me. They're scared of me because they know I've dedicated my life to this cause."

His demands have remained unchanged: an apology, an admission that the company used bullying tactics, and the introduction of a proper, non-discriminatory management policy. And he wants Oki to employ him to oversee the policy.

It seems as unlikely as the Oki workers joining him one morning at his microphone for a lusty version of 'Fight the Power,' but Tanaka says he sings to give people 'courage to fight discrimination’ and measures his successes in small victories.

"Since my firing," Oki has been unable to order a worker transferred to a far-away place, sometimes as punishment. They're afraid they'll create another Tanaka," he says.

When the company rejected his demand that shareholders be allowed to use company microphones at stockholders meetings, he took along his own PA system 'from which I could be heard 200 meters away," he says. The next year the company had microphones for stockholders.

"I will continue as long as my life continues. Look at Oki: they now have 7,000 workers, down from 10,000. The people who harassed me are gone, restructured. I feel sorry for them because they are victims too. It’s the same all over Japan."

For Oki, the issues extend from corporate abuse to democracy and peace. He’s in it for the long haul, as suggested by his song “High Pride” encouraging teachers to resist the order to salute the hinomaru flag.

Let us talk about the importance

of democracy to children.

Let us set an example of living for peace.

Have you forgotten? Only 100 years before,

human rights were worse than now.

Those who struggled achieved what we have today.

Even if you feel you struggle in vain,

It'll make a change in 100 years to come.

David McNeill is a Japan Focus coordinator and writes about Japan for the London Independent and other publications. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus on April 12 2006.